from The Blog of Tim Ferriss

>>ORIGINAL TEXT<<

Deconstructing Arabic in 45 Minutes

Conversational Russian in 60 minutes?

This post is by request. How long does it take to learn Chinese or Japanese vs. Spanish or Irish Gaelic? I would argue less than an hour.

Here’s the reasoning…

Before you invest (or waste) hundreds and thousands of hours on a language, you should deconstruct it. During my thesis research at Princeton, which focused on neuroscience and unorthodox acquisition of Japanese by native English speakers, as well as when redesigning curricula for Berlitz, this neglected deconstruction step surfaced as one of the distinguishing habits of the fastest language learners.

So far, I’ve deconstructed Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, Italian, Brazilian Portuguese, German, Norwegian, Irish Gaelic, Korean, and perhaps a dozen others. I’m far from perfect in these languages, and I’m terrible at some, but I can converse in quite a few with no problems whatsoever—just ask the MIT students who came up to me last night and spoke in multiple languages.

How is it possible to become conversationally fluent in one of these languages in 2-12 months? It starts with deconstructing them, choosing wisely, and abandoning all but a few of them.

Consider a new language like a new sport.

There are certain physical prerequisites (height is an advantage in basketball), rules (a runner must touch the bases in baseball), and so on that determine if you can become proficient at all, and—if so—how long it will take.

Languages are no different. What are your tools, and how do they fit with the rules of your target?

If you’re a native Japanese speaker, respectively handicapped with a bit more than 20 phonemes in your language, some languages will seem near impossible. Picking a compatible language with similar sounds and word construction (like Spanish) instead of one with a buffet of new sounds you cannot distinguish (like Chinese) could make the difference between having meaningful conversations in 3 months instead of 3 years.

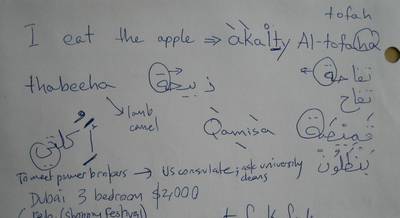

Let’s look at few of the methods I recently used to deconstructed Russian and Arabic to determine if I could reach fluency within a 3-month target time period. Both were done in an hour or less of conversation with native speakers sitting next to me on airplanes.

Six Lines of Gold

Here are a few questions that I apply from the outset. The simple versions come afterwards:

1. Are there new grammatical structures that will postpone fluency? (look at SOV vs. SVO, as well as noun cases)

2. Are there new sounds that will double or quadruple time to fluency? (especially vowels)

3. How similar is it to languages I already understand? What will help and what will interfere? (Will acquisition erase a previous language? Can I borrow structures without fatal interference like Portuguese after Spanish?)

4. All of which answer: How difficult will it be, and how long would it take to become functionally fluent?

It doesn’t take much to answer these questions. All you need are a few sentences translated from English into your target language.

Some of my favorites, with reasons, are below:

The apple is red.

It is John’s apple.

I give John the apple.

We give him the apple.

He gives it to John.

She gives it to him.

These six sentences alone expose much of the language, and quite a few potential deal killers.

First, they help me to see if and how verbs are conjugated based on speaker (both according to gender and number). I’m also able to immediately identify an uber-pain in some languages: placement of indirect objects (John), direct objects (the apple), and their respective pronouns (him, it). I would follow these sentences with a few negations (“I don’t give…”) and different tenses to see if these are expressed as separate words (“bu” in Chinese as negation, for example) or verb changes (“-nai” or “-masen” in Japanese), the latter making a language much harder to crack.

Second, I’m looking at the fundamental sentence structure: is it subject-verb-object (SOV) like English and Chinese (“I eat the apple”), is it subject-object-verb (SOV) like Japanese (“I the apple eat”), or something else? If you’re a native English speaker, SOV will be harder than the familiar SVO, but once you pick one up (Korean grammar is almost identical to Japanese, and German has a lot of verb-at-the-end construction), your brain will be formatted for new SOV languages.

Third, the first three sentences expose if the language has much-dreaded noun cases. What are noun cases? In German, for example, “the” isn’t so simple. It might be der, das, die, dem, den and more depending on whether “the apple” is an object, indirect object, possessed by someone else, etc. Headaches galore. Russian is even worse. This is one of the reasons I continue to put it off.

All the above from just 6-10 sentences! Here are two more:

I must give it to him.

I want to give it to her.

These two are to see if auxiliary verbs exist, or if the end of the each verb changes. A good short-cut to independent learner status, when you no longer need a teacher to improve, is to learn conjugations for “helping” verbs like “to want,” “to need,” “to have to,” “should,” etc. In Spanish and many others, this allows you to express yourself with “I need/want/must/should” + the infinite of any verb. Learning the variations of a half dozen verbs gives you access to all verbs. This doesn’t help when someone else is speaking, but it does help get the training wheels off self-expression as quickly as possible.

If these auxiliaries are expressed as changes in the verb (often the case with Japanese) instead of separate words (Chinese, for example), you are in for a rough time in the beginning.

Sounds and Scripts

I ask my impromptu teacher to write down the translations twice: once in the proper native writing system (also called “script” or “orthography”), and again in English phonetics, or I’ll write down approximations or use IPA.

If possible, I will have them take me through their alphabet, giving me one example word for each consonant and vowel. Look hard for difficult vowels, which will take, in my experience, at least 10 times longer to master than any unfamiliar consonant or combination thereof (”tsu” in Japanese poses few problems, for example). Think Portuguese is just slower Spanish with a few different words? Think again. Spend an hour practicing the “open” vowels of Brazilian Portuguese. I recommend you get some ice for your mouth and throat first.

The Russian Phonetic Menu, and…

Reading Real Cyrillic 20 Minutes Later

Going through the characters of a language’s writing system is really only practical for languages that have at least one phonetic writing system of 50 or fewer sounds—Spanish, Russian, and Japanese would all be fine. Chinese fails since tones multiply variations of otherwise simple sounds, and it also fails miserably on phonetic systems. If you go after Mandarin, choose the somewhat uncommon GR over pinyin romanization if at all possible. It’s harder to learn at first, but I’ve never met a pinyin learner with tones even half as accurate as a decent GR user. Long story short, this is because tones are indicated by spelling in GR, not by diacritical marks above the syllables.

In all cases, treat language as sport.

Learn the rules first, determine if it’s worth the investment of time (will you, at best, become mediocre?), then focus on the training. Picking your target is often more important than your method.

[To be continued?]

###

Is this helpful or just too dense? Would you like me to write more about this or other topics? Please let me know in the comments. Here’s something from Harvard Business School to play with in the meantime…

###